Mass Readings for the 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time:

Zechariah 9.9-10 Psalm 145 Romans 8.9, 11-13 Matthew 11.25-30

“Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me…”

(Matthew 11.29)

Why did Christ come? What was Jesus’ message? His message, both verbally, and non-verbally? That is, what is being conveyed to us in both the words and actions of Jesus Christ?

Obviously, there is His message of redemption through Him, through His sacrifice. What that means is something that the Church too often loses the sense of, and so fails to communicate. Too often worried about its place in society, its privileges and prerogatives; its power. It works to protect itself and so fails to follow Christ’s example of simply putting it out there and trusting in God. Why? The Church has a very hard message for the world, a message that calls it to labour, sacrifice, and die to itself—who wants to hear that?

I found myself the other day watching a university lecture on YouTube and getting more than a little annoyed. It wasn’t that the university professor who was speaking was attacking the Church, because that wasn’t the subject of his talk. Rather, he was lecturing on the contradictions in post-modern thought, the spread of which has led to the craziness we’ve all been witness to in recent weeks.

In the course of his talk, he did a bit of an historical review and talked about the decline of faith in Western Civilization which, of course, principally is about the decline of Christianity. His assertion was simply that the scientific revolution which began in the 16th century upended religious authority, and at the levels of both society and of the individual, science gave a far more believable description of the world than did religion.

It’s actually a very tired thesis. Essentially, what he said, and has been said by the liberal academic establishment for decades, is that Galileo and his telescope, and Darwin and his theory, killed God by making belief in a transcendent deity impossible for any thinking person.

The problem with this argument is there is no evidence. Yes, some atheists (and there aren’t that many of them) will definitely bring up evolution and astrophysics to back the assertion there is no God, but as to the vast majority of people, one can’t say their lack of faith, or more accurately, lack of religion, is demonstrably because they all have studied biology and physics for themselves and come to a logical conclusion. Correlation is not causation; sometimes it is simply coincidence. To say science, what was largely developed by the Church through the Medieval period, is the enemy of faith is ridiculous. The Church was the patron of science. And science, we must remember, is not a philosophy of life, an ethical code, it is simply a systematic method of inquiry.

illustration, detail of Astronomer Copernicus, by Jan Matejko (1873)

A better analysis will look to the so-called “Reformation” and the moral crisis among the ruling class of Europe as a more likely source of the decline of faith. The ethic of individual conscience as asserted by Martin Luther gave license to everything eventually. To escape the authority of the Church in moral matters, an appeal was made to a new emerging authority: science. And to science we’ve been yoked ever since.

This isn’t to say that we are “scientific” as a culture. Hardly. If the basis of science is logical, rational inquiry, we seem to be in the midst of a cultural moment that is quite contrary to this: emotion is the hallmark of today’s rebellion.

I don’t think it is much of a revelation for anyone if I were to make the observation that human behaviour, human decision-making, is driven by emotion rather than rational analysis. If allowed, unrestrained by moral disciplines derived from reason, our emotions will push us to satisfy primal appetites at the expense of morality, and “reason” simply becomes our ability to “rationalize” our decisions, justify them to ourselves at first, and as we grow more aggressive, bully others into agreement.

Live in a society that says “be yourself” then defines the self as little more than a bundle of appetites in need of satisfaction, then little wonder that people quickly turn from a religious system that says you are more than your urges because that means a life of self control and disciplined thought.

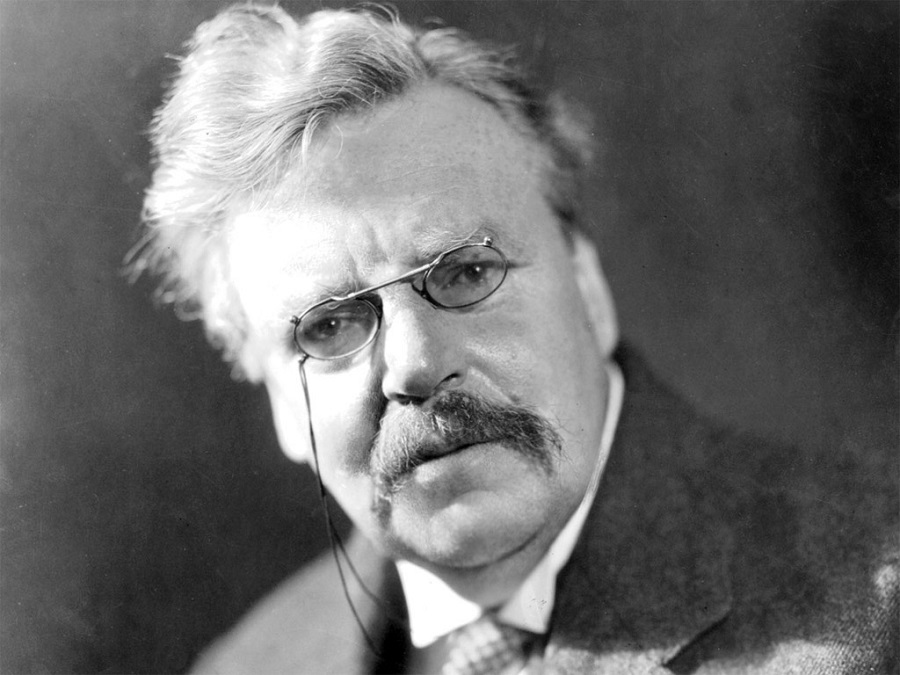

As the great G.K. Chesterton famously wrote, “Christianity has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and not tried.” (What’s Wrong With The World, ch. 5)

― G.K. Chesterton

So, to be clear, Jesus did not come to teach us quantum mechanics, or to map the human genome; he was not concerned that we should grasp the rudiments of chemistry or develop nuclear energy. God knows that we are capable of all those things. We are made in His image; I think that implies quite strongly that we have been endowed with an imaginative capacity for invention and a rational faculty for contemplating the nature of things. We didn’t need help with that.

What we need help with is in maintaining our moral centre; not the matter of knowing right from wrong, because the fall of Adam and Eve was in taking the fruit from the tree of knowledge of Good and Evil. In that foundational myth which explains so much about our human nature, our eyes were opened really to just evil. Having known God as a friend, we knew goodness. Turning from God in disobedience, and eating the fruit, this was the discovery of evil and becoming drawn to it.

Jesus tells us, but more powerfully shows us by his actions, which find their fullest expression in the sacrifice upon the cross, that we can cast off the burden of sin through Him, and take up a life-giving work of self-giving in love according to truth. Through Him we can reject evil and be free to enter the embrace of God, forever.

It’s not for nothing that Jesus describes following him in terms of the putting on of a yoke. A yoke is an ancient tool; usually it was made of wood, and carved to fit the neck and shoulders. Its purpose was to actually to prevent pain or discomfort while increasing the capacity for work. Animals were yoked so that they could pull ploughs or wagons more efficiently and more willingly. Human beings had yokes to enable them to carry things, often heavy buckets of water, or baskets of stone or wood. It is more than a coincidence I think that a yoke is worn across one’s shoulders, and is therefore reminiscent of the crossbeam of a cross of crucifixion that many carried to their public executions.

A yoke means “work.” One doesn’t wear a yoke as a fashion accessory. We will not see such on the runways of Paris or Milan any time soon. No, Jesus is saying to follow me is to agree to work.

A yoke also implies subservience. We can find reference throughout both the Bible and our literature more generally that uses the yoke as a metaphor for submission (“the yoke of oppression”). In this case, Christ is asking for us to submit to Him. However, lest we believe that we can cast off His yoke and carry on through life entirely unburdened, the hard truth is that we are all yoked to something: an ideology, perhaps; but more likely something less systematic and usually rooted in our brokenness. Many yoke themselves to sin: greed, lust, gluttony, and so these become what we submit our lives to, and we are miserable for it.

Jesus is well aware of the outward lack of attractiveness of His offer. Those who are wise in this world know better: the sacrifice and discipline to attain what cannot be seen, cannot be touched?

But even we who have learned to take the eternal, the transcendent and the spiritual seriously, we too struggle at times. By our reason guided by faith, it ought to be simple decision. As Saint John Henry Newman put it,

“Viewing it as a practical point, the end of the whole matter is this, we must be changed: for we cannot expect the system of the universe to come over to us, the inhabitants of heaven, the numberless creations of Angels, the glorious company of the Apostles, the goodly fellowship of the Prophets, the noble army of Martyrs, the holy Church universal, the Will and Attributes of God, these are all fixed. We must go over to them.” (Sermon II, Parochial and Plain Sermons, Vol. VII)

So, be mindful to put on His easy yoke, even if it chafes at times, and when people ask you about this faith of yours, be sure to tell them it goes well beyond a Sunday Mass followed by a light lunch. It is work, work of the soul to prepare it for God’s coming; work of this world to bring our loved ones and strangers to join us, make known the easiness of labour for God, the lightness of the burden that comes with redemption.

Amen.