Mass readings for the 3rd Sunday of Lent:

Exodus 3.1-8, 13-15 Psalm 103 1 Corinthians 10.1-6, 10-12 Luke 13.1-9

The message of Lent is one of repentance.

But when we hear the priest, the preacher, the prophet all crying, “Repent, repent!” What do we understand? What are we being asked to do?

Well, you’ve heard “repent” defined by me and others over the years: it means “return” or “to turn back” and follow the path God defines for us that leads to eternal life.

Our challenge is to know and follow that path, and there is some urgency to this. Jesus speaks to us today about the uncertainty of life in this valley of life overshadowed by death.

Bad things happen. We hear today in the gospel of two incidents: people dying in an incident with Roman authorities; the collapse of a building.

I think most people are aware on some level of this harsh reality, and so, most are searching for meaning and purpose so that whatever amount of life we’re afforded, we’ll have a sense that we were living our lives somewhat well, properly oriented toward goodness when the end arrives. For Christians, the further hope is that the end of this road is an exit onto eternal life.

What Jesus today warns us not to become distracted from that focus. Today we see a lot of people substituting a false sense of righteousness for authentic conversion, of making the latest cause celebre the foundation of their hopes when the true source of our salvation is not in the passing events of our day, but as our Lord teaches, it is found in a relationship with the eternal mystery of God, in his love, in his truth.

We don’t want to be like the Hebrew slaves who fled from the evils of slavery in Egypt only to be lost in the wilderness, forgetful of what the journey to the Promised Land was really about – not simply the ending of their slavery (which was certainly good), nor the inheritance of land, but the exodus is about a new and true life had in a community of faith worshiping the only true God who is light, life and love.

So, two recent events of the time are highlighted for us in this story of Jesus’ encounter with people in Jerusalem: a massacre and the collapse of a tower killing many.

The first has people coming to Jesus for comment; it’s the recent massacre of Galileans, which one would think would hit close to home from a man from Nazareth. Now, we don’t know the details. These are lost to us. The reference is brief – Pontius Pilate sent out his troops to deal with some unruly people from the Galilee.

Galileans had a reputation as troublemakers. Fellow Jews to be sure, but they weren’t Judeans, but rather cousins of a sort, who had a predilection for causing trouble with the Romans that made life difficult for everybody.

The reference to them having their blood mingled with their sacrifices indicates that whatever happened it was in or near the precincts of the Temple. In any event, it would be regarded as an outrage by the people of Jerusalem even if it wasn’t an action against them – Pilate violated the sanctity of the Temple in having his troops carry out this small massacre. The Galileans, for their part, may have provoked it.

These people of Jerusalem who’ve come to Jesus, they’re looking for a comment; and likely expecting a condemnation of either the Romans or the troublesome Galileans.

“Jesus, aren’t you as outraged as we are?” “Doesn’t this infuriate you?”

It’s something like reporters looking for a comment from a public figure on a current controversy, international crisis, national scandal, what have you, but above all looking to have the emotions of all involved further stoked by what will be said. Will Jesus feed the outrage?

If we’re asked about what is going on in Ukraine right now, I think we know what we’re all supposed to say: it’s outrageous and can’t be condemned strongly enough. But what does that accomplish? How does that advance our understanding of what’s going on in the world and how we ought to be living our own particular lives.

We must be cautious of looking to find satisfaction in an emotional response; in believing that a sense of outrage makes someone a good person, a righteous individual.

Being angered by evil doesn’t make you good. Indeed, there is every danger in indulging in the collective outrage that you will be carried away into greater evils, compounding the problems, multiplying the troubles out of ignorance of the complexities of a situation that most of us have only become aware of in recent weeks.

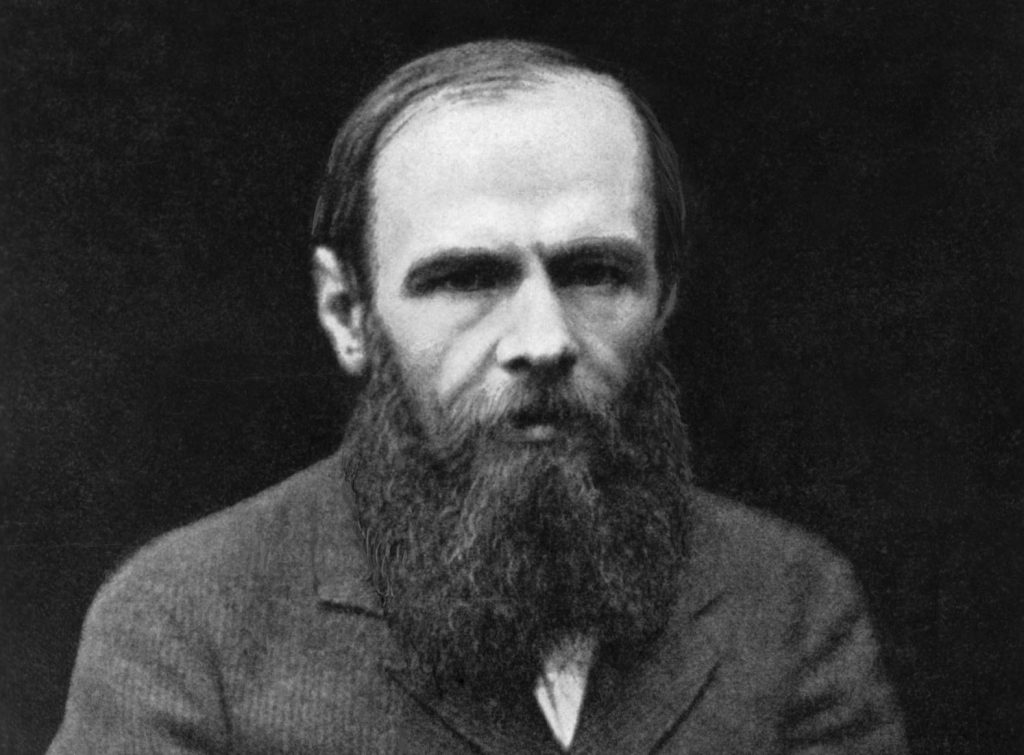

Calls to destroy the careers of Russian opera singers and musicians working abroad is hardly constructive – most of them are trying to preserve their careers while not bringing the Russian state down on family and friends back home. Pulling Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff from the playlists of classical music stations, or removing Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky from library shelves is not going to help. Indeed, that impoverishes us.

And what about the last cause we were all up in arms over? The last thing that we were outraged at? We mustn’t careen from crisis to crisis responding in outrage, and then forgetting it all when the next thing comes along. We as Christians are called to demonstrate a certain emotional sobriety rooted in grim awareness that this world is a place of trial.

It’s amazing what Jesus says when asked about the Roman massacre of the Galileans, something morally outrageous. This in many respects is a trap into which Jesus could fall; is he going to speak against Roman authority? That would certainly give ammunition to his enemies, make it so much easier to justify their evil plans directed against him. Is he going to alienate his followers by agreeing that the cruel death visited upon his countrymen somehow reflected a defect in their character?

Well, he doesn’t respond as people likely expected. He won’t answer in such terms. Rather, he begins making comparisons to another tragedy, the collapse of the Tower of Siloam.

We don’t know much about the Tower of Siloam. It fell over, and killed people. As to the cause of the collapse, we’re quite in the dark. Incompetent engineering or slipshod construction, poor maintenance, we don’t know.

Why would he connect these two events?

Well, if you listen to what he says, he talks about sin as the ultimate context for thinking about both the victims of Roman violence and of the more impersonal tragedy of what was an accident; but it’s not the sinfulness of Roman legionaries, or of the ancient builders, but the sins of everyone.

This is the world we live in is what he is pointing out. A great many lives will come to an end through misadventure, accident, violence, war, famine, even as we pray for our end to be peacefully in old age. Are we prepared? What is the relationship we have with God?

As much as it is important that we be people of compassion toward the suffering; and that we do reject and fight against injustice and cruelty, our priority must always be toward personal righteousness, being rooted in the love and truth of God because that is the necessary preparation for dealing with the outrages of this world with calm and humility; it will make us ready for when towers topple over on us.

Like the fig tree that fails to bear fruit, we’ve got to do more than just stand here and be. We must bear good fruit; not the bitter fruit of anger but the sweet and satisfying fruit that comes of mercy, compassion, humility, generosity, all the virtues we see in our Lord who is the beloved son.

Conform yourself to Christ as a son and daughter adopted by God, and trust that it is the Lord who will work vindication and justice for the oppressed through those who are faithful, obedient, and humble in their service. God will show the way for us; as St. Paul reminds us, he instructs through his Holy Word, it is for us to listen, obey and watch out that we do not fall even as the world collapses around us.

Amen.