Mass readings for the 26th Sunday in Ordinary Time:

Amos 6.1a, 4-7 Psalm 146.6c-7, 8-10 1 Timothy 6.11-16 Luke 16.19-31

Today we have Jesus continuing in his teaching on the problem of disparity of wealth, the need for charity, and how each of us bears mutual and personal responsibility for each other. And this really is a personal matter, and not to be a delegated one. It’s been our dependence upon agencies and state-run entities for now several generations that has bred out of too many the instinct or intuited sense of obligation we have toward others as a personal matter. We need to remember: in our fallen nature, we aren’t disposed to be generous. Our default is fear, not trust, to be selfish and not sharing. And yet, Jesus tells us the way to heaven is in our trust in God, and our sharing of ourselves through him. His sacrifice shows us not to be afraid of self-offering for the sake of others.

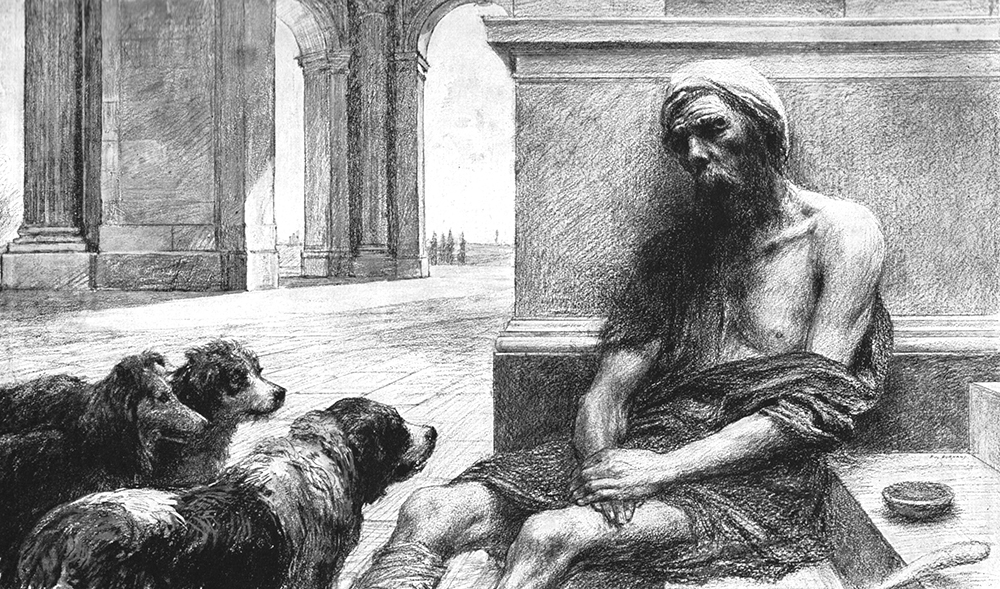

And as our God is a god of relationship, that is, he knows us, and cares for us, not as the undifferentiated mass of humanity, but as individual persons, so too are we to relate to others this way. In the parable we just heard, the poor, sick man is known – his name is Lazarus. God knows him, and we trust that Lazarus knows God even in the midst of his suffering.

The “poor” get abstracted away from us; we who are fortunate not be among their ranks. The poor become a political problem, and so, a matter for government. Which isn’t itself wrong – those who govern have that custodial duty to see that our society does not devolve into a vicious dog-eat-dog dystopia. Yet, what has happened is that the poor, like so much of society under the liberal technocratic regime, they become a demographic category. Our system chops up the public into all kinds of discrete communities and as a result creates ever deepening divisions who then have their political champions, and enemies. We forget our shared humanity, and the need for solidarity as one people, The poor have become a “community” apart, a separate constituency. As an identified group among groups, they are exploited in our politics by the powerful, they become the focus of an industry in which both private and public entities have an interest that often doesn’t coincide with the best interests of the poor themselves.

Years ago, when I was working in local government as a councillor’s assistant, the province of Ontario revised the welfare rates. A public meeting was called to discuss the impact on the region and municipality. I went to that meeting with my boss, Councillor Diane Holmes. There were no poor people there. There were representatives of government departments and public agencies, there were the reps of different advocacy groups, and a lot of landlords (and you might call them “slumlords” – they owned the substandard housing so many of Ottawa’s poor lived in, the rooming houses, and so on); the public housing people were there too.

All of these groups had a stake in the poor. Their employment, their income, their living, their status as community leaders, as important people in the government bureaucracy, in some way was derived from the poor. And I remember how the proposed changes were discussed it struck me that the discussion was about how it was going affect all of them, and only secondarily, did they talk about the poor themselves.

Now, at that time I was also very involved with a downtown street ministry and food program. I managed the pantry for something called the St. Luke’s Lunch Club – we served breakfast and lunch on weekdays, and provided a contact point for public health nurses, and other services. Anyway, I knew poor people, street people, working poor, single moms on welfare, middle-aged men who lived on the street addicted to alcohol and worse, male and female prostitutes, and so on. Really, all the people we were discussing at that public meeting. Yet at that meeting, none of the poor had names; when the next day I was at the lunch club, everyone had a name. And where at the public meeting, the poor were a constituency, a client group; when I was at the parish kitchen that made the daily breakfasts and lunches that were served, I recognized a lot of these people as neighbours, as folks I saw everyday in my community, and who knew me. I had no sense of us and them, of there being some great divide. I was just lucky to have a job that paid well enough to have a nicer apartment on a safer quieter street in the same neighbourhood they called home.

When later I did home visits, much as the members of the St. Vincent de Paul society do in our parish, to assess needs and figure out how to help with the few resources the church and city had, I came to see the absolutely despairing situation of families and individuals stuck on the welfare rolls. In those crummy little apartments they lived, bored, stoned, depressed, lonely, frightened, etc.

Now, don’t misunderstand me. The poor are no more apt to be virtuous than the rich wicked. Sin is a universal among men and women, and a lot of poor people don’t help themselves with the bad choices they make. But I do remember how distinctly different it was when they came to know me by name, and they had the sense that I knew them as something more than a problem to be solved, even a threat to me, but as a person who has a name and a story.

For some, that realization that somebody else could see more in them than an example of a sad statistically reality gave them hope that well, maybe they are more than what their welfare cheque said about them. And that opened a window through which grace could enter; and they were changed. For some, they went back to school, got their high school equivalent, and started to find a way out of the world they were trapped in. Others, well, some are too far gone, drugs and alcohol having taken their toll, but they could by relationship recognize in themselves that they too were God’s children, and could live in hope in an ultimate reward – and so, they grew kinder, and astoundingly more generous with the little they had. I always tell the story of this one fellow named John who kept himself warm through an Ottawa winter by layering himself in sweatshirts and hoodies. He’d have 8 or 9 of them pulled over his rather ample bulk – he was big, and this arrangement of sweaters progressively covered less and less of his body as the layers grew such that the last of them barely covered his belly. A parishioner was distressed to see him one day when the temperature was way down in the minus 30s, and so she went to Sears and bought the biggest parka she could for him in the hopes it would fit. And it did. And Tiny was really grateful, he didn’t speak much, but I could tell he was touched by this. A few days later I saw him, in the freezing cold, with probably ten sweatshirts on, and no parka. I was concerned he’d been robbed – that happens, the street’s a tough place. I asked him about it, and he said, no, everything was fine, he’d given it to a friend who he thought needed it more, that his multiple hoodies did him fine.

The rich man and Lazarus, are extreme examples. Lazarus is not only poor but also sick and so, incapable of earning a living; he survives from the charity of others who aren’t mentioned but are certainly implied in the parable. These relationships, among the people on that street, the passing slaves on their errands, the housekeepers and tradesmen who went past every day, and in passing would drop him a coin, leave him some bread, bring him some broth, and likely did so at a definite cost to themselves, these were human relationships born of concern for another that involved sacrifice by one and thanksgiving by the other.

The rich man doesn’t work anymore than Lazarus, except that he likely meets with the managers of his estates to check the tallies of his rents, his crops, the return on his many investments. His relationships were about himself, his money, his wealth, his status in society, but none of them served to reveal his humanity – he’s a man with no name to God.

The two lived their lives literally yards away from each other, and yet had no connection. And in death they are also parted. The rich man asks that Lazarus bring him relief from his suffering in hell; ironic that he never offered Lazarus any relief in life. He recognizes too late that Lazarus had a potential place in his life; that the sick beggar held for him the possibility of some small sacrifice that would have opened him up to God and the greater possibilities of a life lived in Christ. But he missed his chance.

We have our risen saviour, back from the dead, to tell us that kindness won’t kill us; rather, it will bring us to fullness of life.

Amen.