Mass readings for the 31st Sunday in Ordinary Time:

Malachi 1.142.2, 8-10 Psalm 131.1-3 1 Thessalonians 2.7-9, 13 Matthew 23.1-12

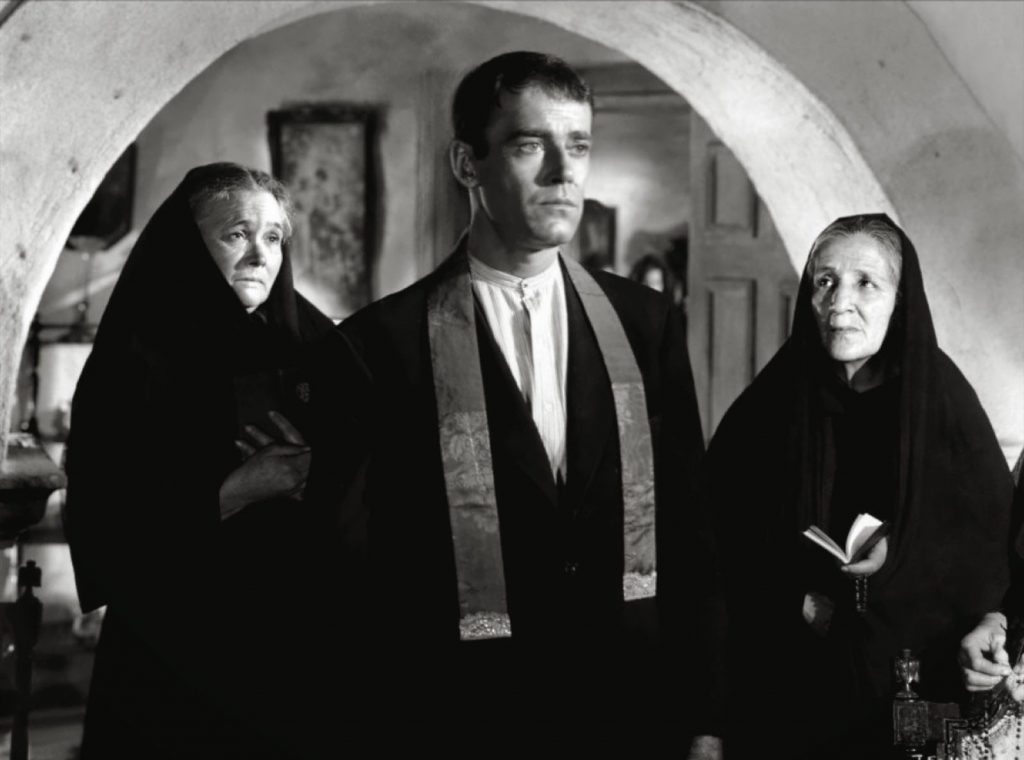

I can’t help but wonder what crossed the minds of my thousands of priestly colleagues when they all read today’s scriptures in preparation for this weekend’s masses.

The message should give us all pause, and maybe a little trepidation: the prophet Malachi condemns unfaithful priests for leading so many astray having “corrupted the covenant.” Now, in Saint Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians, we hear a more cheering thought on what motivates the great travelling evangelist. It’s what ought to be at the heart of my ministry as pastor, and that of the ministry of all the ordained and the religious, but I would say also, the priesthood of all believers: acting out of love for God and concern for God’s people, and nothing else.

Then we have our Lord; Jesus reiterating what Malachi had said centuries previous: the religious leadership do not serve the people but themselves. Their positions of authority were a vehicle of private ambition, political power, and personal justification. And so, not surprisingly, the religious system of the law and of the temple meant to sustain faith, was perverted and turned into a spiritual dead weight for the people.

What can we say of today’s leadership and the spiritual state of our society? Do we live by God’s Word and Christ’s sacraments as priests and people? Or do we use them for our own ends? Do we give meaning to our lives by living a life of authentic Christian faith? Or do we, by clever parsing of the scriptures, and disingenuous interpretation of our traditions, validate the compromises we make with the world to ease our fears of judgment or give us licence to satisfy our worldly desires?

That’s what happened in ancient Israel. The prophet Malachi spoke in the aftermath of Israel and Judea’s fall, exile and return to the ruins of Jerusalem. The history of Israel’s decline and fall was still fresh in everyone’s memory, and the continuing corruption was easily seen by Malachi and others in widespread moral laxity – the attitude being, well, we know acting this way wrecked everything but the work of repentance and rebuilding is just too hard. Later when Jesus faced his enemies among the religious leadership, they had gone in the opposite direction of oppressive religious legalism; and in both instances it wasn’t being driven by an earnest desire to nurture a life sustaining faith in others, but rather to maintain control over the institutions of religion, and so, keep their authority and privilege; keep the money flowing into the coffers; to appease political interests, etc. – and they did this with a sense of undeserved moral superiority, and frankly, with contempt for the people. They stopped working to make them holy, but rather to keep them either distracted by the indulgence of their sins, or in terror when in condemning them for their transgressions.

We must ask what has happened to us as a society. We see a collapse of faith and so, a civilizational crisis whose metrics we all know: declining marriage and birth rates, an unbalanced economy with massive debts, growing unaffordability of necessities in supposedly developed countries, a confusion in our identities both collectively and individually that is beginning to resemble the chaos and division at the tower of Babel.

And there is anger, frightening anger among so many, and a desire to find the culprits. And woe to those who do bear some responsibility for where we are today, because they may become the scapegoats for all our troubles. I hope not because we all need to recognize our own part in this, and, well, repent and return to God.

Journalist and essayist David Warren, a convert to Catholicism like myself, but a man of far greater experience and learning, offered some thoughts on the rising tide of vicious antisemitism we’ve seen of late (I invite you to read his short piece, and I’ll post it with my homily on our website). He sees it as an expression of anger at God. And in that I made a connection to our general spiritual crisis.

His reasoning proceeds from what we as Christians know and acknowledge about the Jewish people: they are the chosen; and not arbitrarily, but “They are chosen in divine revelation, and shown the direction they must follow, or fail to follow. This makes them different, unique, distinct from all the other ancient (peoples) that we study.”

We need to recognize how radical a departure it was for the Hebrews to set off on their spiritual quest for the Promised Land; how “The spiritual and moral sensibility that emerges, the structure of commandment, marks them radically apart.”

What we as Catholics take from this example is that God not only calls, but he compels us to take our own journey, as individuals, but also as a Church. But what compels is not his will, or his wrath, or his promise of a paradise at the end of the road; but rather it is the truth of what we find in his word, and the sometimes-painful response we have to it.

For sceptical atheists who believe that we have made up this God we worship, the famous psychologist Carl Jung had the excellent answer: “We do not create God, we choose him.” That is, we encounter through uplifting religious experience, or distressing spiritual crisis, what is unavoidable, the truth, and we must then respond, give an answer, make a choice.

For us, we understand this as a choosing between obedience to the good shepherd who guides, or to run from his rod that chastises us, and his staff that restrains us, to be free, wandering where we want through the world, through the valley of the shadow of death but without any shepherd.

We find today a great anger among those who feel their wills thwarted in their desire to be free on just those terms. And there is anger as we are experiencing the consequences of our flouting of the moral law – but you know, the misery is never attributed to the walking away from God. Rather there is resentment toward God, and perversely toward the faithful whose very existence is seen to be mocking the secular-minded, the progressives and the woke. We don’t need to say a word to make them furious. How convenient to have a target for this wrath; there is the Jewish people who are an ever-present reminder of the reality of all human existence, of how we flourish and flounder as a people according to our relationship with God.

The Church, in the modern era, has at times served as the Jews’ proxy in the anger toward the hard truth of life. Churches burn, priests assaulted, religious killed, Christian children taken, men murdered and women raped, and this happens around the world today, and even here albeit to a much lesser degree of violence.

I’ve told the story on other occasions of a woman making an appointment to see me when I was serving at St. Patrick’s church downtown. She took the hour to rail at me about the evil of the Catholic Church. A few years later, however, she became a Catholic.

What I come to sense about this widespread anger, but also the despair and discouragement that have given rise to it, is that it does come from a crisis in faith, but not a faith in God, or more accurately a faith in the God known in Jesus Christ.

The god who has failed so many was the idol of secularism and all its different iterations of liberalism, progressivism, woke-ism. This is the god who supposedly liberated so many in the social revolution of the past sixty years, and has now abandoned them, or more accurately proven to be no god at all, and so as phony as the infamous golden calf.

The Church stands today at a crossroads in its own continuing journey, as the Holy Father Pope Francis tells us, we are seeking a synodal way forward, that is to walk together into the future. But there needs to be agreement as which way we’re to go. If it is to follow the great mass of people who have hitherto been wandering aimlessly in the spiritual desert of the modern world, seeking what pleasures and distractions might be found, then this is to lead the faithful along with the unfaithful into the wilderness to die. The priests who so direct us, the leadership that merely runs to front of the crowd to give the appearance of leading, they will be rightly, to borrow the words of Malachi, despised and abased before the people when they at last realize how they’ve been led in circles and come no closer to the Promised Land, and may be further from it than before.

Bishop Robert Barron, before setting off for the recent Synod on Synodality, wrote several essays detailing his thoughts about the expectations that had been raised in the consultative process that preceded the synod. He detected some of what I’ve spoken about; there was certainly anger, but also how there was a growing appeal to the idea of inclusivity as a guiding principle of the synodal way. And there is an appeal to this image of all of humanity, in all its variety, walking together. We might be comforted initially by having each others company, yet, as I said, end up walking in circles.

Barron said correctly that inclusivity as a value has never had a place in Catholic tradition. He points out that Jesus was radical in his welcome to all, but that all who accepted his invitation were called to the hard work of real discipleship and sincere conversion; and of the ongoing invitation the Church offers, he wrote,

“…you are being invited, not into an amorphous collectivity, but rather into a defined community, into a family with a moral and legal structure, into the mystical body of Christ. If, therefore, you were to say, ‘I demand to be included, but I have no interest in conforming myself to Christ’s demands, to the teaching of the Church, to the expectations of the community,’ you would find yourself in an untenable position.”

As Barron says elsewhere, all inclusion requires exclusion. We can have Christ in our lives, and so be included into his Church, but this means the exclusion of our own ambitions and desires in deference to Christ’s mandate of self-sacrificing love. We cannot make of the faith what we will, exalting our ideas of righteousness over the express teaching of our Lord, whether those fall on the side of moral relativism or to the side of religious legalism. To do so would, on the one hand, makes King Herod and his notorious children saints, on the other, it’s to admit the Pharisees were right all along.

Rather, we must die to ourselves, be humbled and forsake being exalted, and in our humility then be lifted up to the very presence of God, and to live in joy forever.

Amen.

Links:

God and the Jews, by David Warren

Inclusion and exclusion, by Bishop Robert Barron