Mass Readings for the Feast of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph:

Genesis 15.1-6;17.3b-5, 15-16; 21.1-7 Psalm 105.1-6, 8-9 Hebrews 11.8, 11-12, 17-19 Luke 2.22, 25-27, 34-35, 39-40

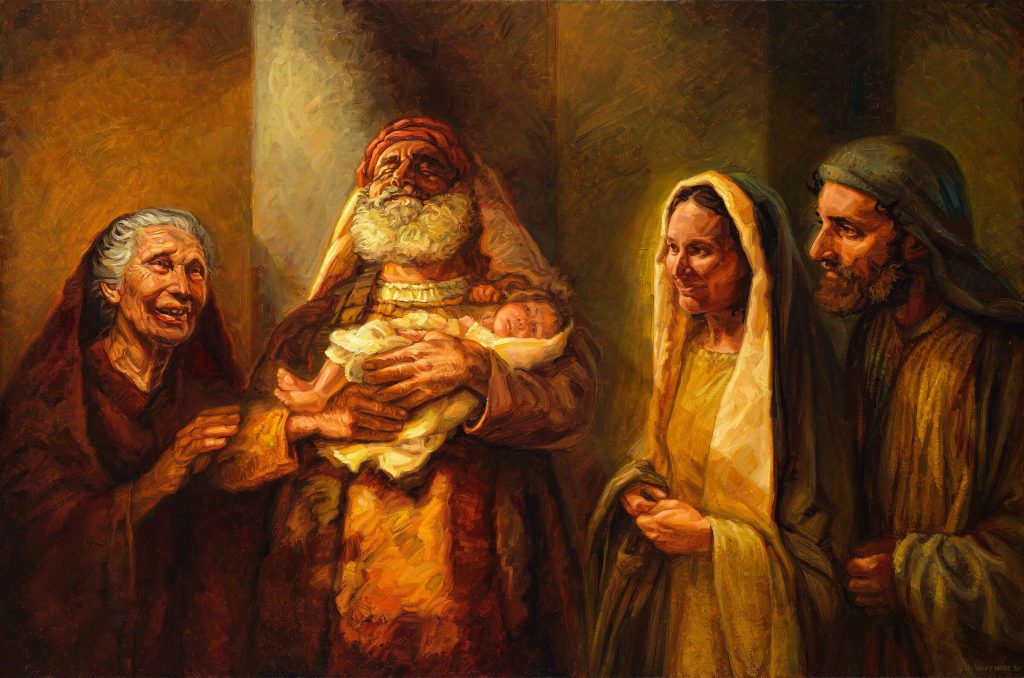

It’s fascinating to consider Simeon and Anna, those two aged denizens of the Jerusalem Temple, who daily went to that great house of God. In all the crowds who would be coming and going in the fulfilment of their religious duties, among them Mary and Joseph with the child Jesus, it is these two who recognize the baby for who he is.

Both were guided by the Holy Spirit to baby Jesus, but that guidance did not come randomly or spontaneously to two ignorant people. Anna and Simeon knew their scriptures and lived in anticipation of the Saviour’s coming. It’s through this knowledge of Israel’s history, a great familiarity with the words of the prophets, that the Holy Spirit could work through the words of sacred scripture to tell them this is the day when the prophecies begin to be fulfilled. These two represent Israel’s past, her heritage, her legacy of wisdom, knowledge and prophecy; and God honours them with this visitation with the Lord in the Temple.

We live in a curious time in which the current wisdom among the elites is that we have nothing to learn from the past aside from history telling us how awful people were. Indeed, for whatever virtues they may appear to have, they are essentially deplorable. There is so little worthwhile of the past that we ought to actually change it. Now, that is impossible: the past is the past; but we see efforts in popular entertainment, in government narratives around issues such as those involving race; and in the academic study of history itself, to simply change what we find unappealing or not useful for the current day agenda.

So, Henry Dundas goes from being a hero of the abolitionist cause to being a collaborator in the transatlantic slave trade. He’s now a villain because his approach to ending slavery doesn’t accord with the opinions of some people today who are two centuries removed from the situation. And as we’ve lately learned, Toronto city staff have allegedly been deliberate in withholding from that city’s council peer-reviewed scholarly assessments of Dundas that refute the slanders made against him. These have led to this crusade to remove his name from every street, landmark and city facility.

We get historical dramas set in Tudor England with Ann Boleyn played by a black actress with the justification that while this wasn’t at all accurate to the period, it’s the way it should have been; and, this makes the history more inclusive, allows more people to see themselves in the story, even if it means distorting history. This is simply condescending, and insulting to those miscast, or misrepresented in this manner. It says that historical dramas that would be appropriate to racially diverse casting aren’t worth making—how about a dramatization of the trial of Joseph Knight, the escaped Jamaican slave whom Henry Dundas served as legal counsel? Knight’s story is the very stuff of great drama, and a significant chapter in the history of Scotland, and the western world.

It’s evil to be teaching people through entertainment, especially an increasingly uneducated and historically illiterate western population, things that are simply not true.

Alarmingly, this has been going on in Christianity, whose message is that the truth sets humanity free. There have been ongoing efforts for a generation and more to reinterpret the biblical story in terms of modern categories and concepts; and so, imposing on the text of the Old and New Testament, the words of the prophets and the message of the gospel, meanings that hitherto no one had seen, nor can really be argued to have any basis within what’s actually written.

There are certainly many ways to approach a biblical text, and as a preacher I have been taught, and so use, these. We can read a story allegorically: Christ’s feeding miracles can be seen as illuminating our understanding of the Eucharist, for example.

Another common approach, and one I tend toward, is historical exegesis. That is, we gain insight into the meaning of a text by investigating what was going on in the world, both in terms of when the story took place, but also with reference to when it was written down.

It’s a commonplace observation of scholars of the gospels that the presentation of the story of Jesus by the gospel writers is both a record of events, but that each of the writers reflect certain theological priorities based on who their intended audience was, and what their circumstances were. So, for example the gospel of Mark is understood to have been written for a non-Jewish audience living outside the Holy Land some time around the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Mark tries to help his readers make sense of what is going on in the world at that time with reference to the bigger story of Christ coming into the world.

That we know that, helps us read the gospel of Mark accurately, understanding why it’s different from the other gospels, what it has to contribute to our knowledge of Jesus and our comprehension of Christ.

But this is something that many in the broader Christian community, and in the Catholic Church as well, are tempted to put to one side for the sake of pushing an agenda, being an activist with respect to particular current day causes.

And it’s not that a Christian can’t have concern for refugees, the environment, the homeless and unemployed, etc. It’s just that we must remember and respect the source of our wisdom is the actual word of God, and we cannot opt for the humanly edited and extirpated version that too many are tempted to offer.

I remember a number of years ago my mother, relating with distinct disapproval, the fact that her parish’s annual Christmas pageant was centred around the idea that the Holy Family were homeless. The director that year, looking to be “edgy” as is the fashion, set the nativity scene, not in a stable, but in a dumpster, to underline the connection between the biblical story to the new narrative of social concern over homelessness.

If you have followed the news leading up to Christmas, you may have noted the attempt to characterize Mary, Jesus and Joseph as Palestinians living in “occupied” territory.

And you may also have heard about a progressive Catholic priest in Italy setting up a nativity scene in which Joseph has been removed to the far side of the stable and Jesus is given two mothers.

Again, I think we can discuss difficult issues as Christians, but we cannot change the story from which we gain our sense of identity and meaning as a people of faith. It’s not for us to shape the story, and make it fit comfortably our sense of ourselves and have it serve our limited ends, but rather we are to be shaped by the story, and to leave the comfort of self-contentment, pick up the cross and follow this story where it will lead us.

I mentioned Christmas Eve that the seemingly straightforward nativity story has a lot going on in it, and that it has an uncanny quality—for all that is familiar in it, there is something strange going on and it is for us to study and meditate upon it so that it can reveal to us something of its mystery.

You can’t do that if the story has been adulterated, abridged or amended by the world, if the stable has been carted away, or the Holy Family transposed into another time and situation.

It’s for us to keep the story, tell the story, and be faithful from generation to generation in doing so. We are keepers of a treasure, and custodians of a mystery. So, we shouldn’t meddle with what we can’t entirely comprehend, but carry out our duty with the knowledge that it is by this story and the Holy Spirit that we are made descendants of Abraham, the father of faith, and heirs to the promises of Christ our Saviour.

Amen.