Mass Readings for the 6th Sunday in Ordinary Time:

Leviticus 13.1-2, 45-46 Psalm 32.1-2, 5, 11 1 Corinthians 10.31-11.1 Mark 1.40-45

Pope Francis preached on today’s gospel text – the healing of the leper – back in 2015, taking the opportunity to underline our particular duty toward the marginalized. He said, “The Gospel of the marginalized is where our credibility is found and revealed.”

Indeed, we have a definite mandate to go out into the world in search of those on the margins of society, on the margins of the Church, and to bring them into the fold, into the family of faith. Yet we must be careful in our outreach, because not all the marginalized are the same. They come in different categories. And the Holy Father warns us about confusing these categories. He said that this compassionate outreach “… does not mean underestimating the dangers of letting wolves into the fold” through misapplied compassion. Rather it means “welcoming the repentant prodigal son; healing the wounds of sin with courage and determination; rolling up our sleeves and not standing by and watching passively the suffering of the world.”

There are those who marginalize themselves by living sinful lives. In his homily, Pope Francis cited Jesus’s famous encounter with the woman caught in adultery, about to be stoned by the crowd. Our Lord rescues her, but he sends her on her way with the admonition to “sin no more.” That’s a particularly difficult ministry today. How dare Christians comment on such things that are none of our business; and indeed, in this cultural moment, which will surely pass, these matters aren’t understood in moral terms, but rather those of human rights and dignity because today the secular mantra is to “discover who you are” and live that out with integrity. So, those called to this ministry need special charisms, and graces to carry out their work.

We have the poor, who as Jesus tells us, “are always with us.” And to be accurate about where this concern lies, these are not “the poor in spirit” but people beset by poverty – they are the many who we can say are more sinned against than sinning, often suffering from hunger, lack of shelter, and other necessities of life. From their own sin and the sins of others, they must be spiritually healed, but also helped in a material way. And the Church has since its outset, in the inauguration of the office of deacon, always had this ministry. At St. Augustine’s, this is reflected in the work of the parish, but also our societies: the Knights of Columbus, the Catholic Women’s League, are two examples, but most especially the St. Vincent de Paul Society whose particular and exclusive work is with the poor, bringing them material assistance as well as spiritual comfort. From my own experience in street ministry in Ottawa, those involved in the front line, as it were, going to the rooming houses, into public housing projects, slum apartments, this can be dangerous; and it requires certain gifts of the Holy Spirit in abundance, fortitude coming especially to mind.

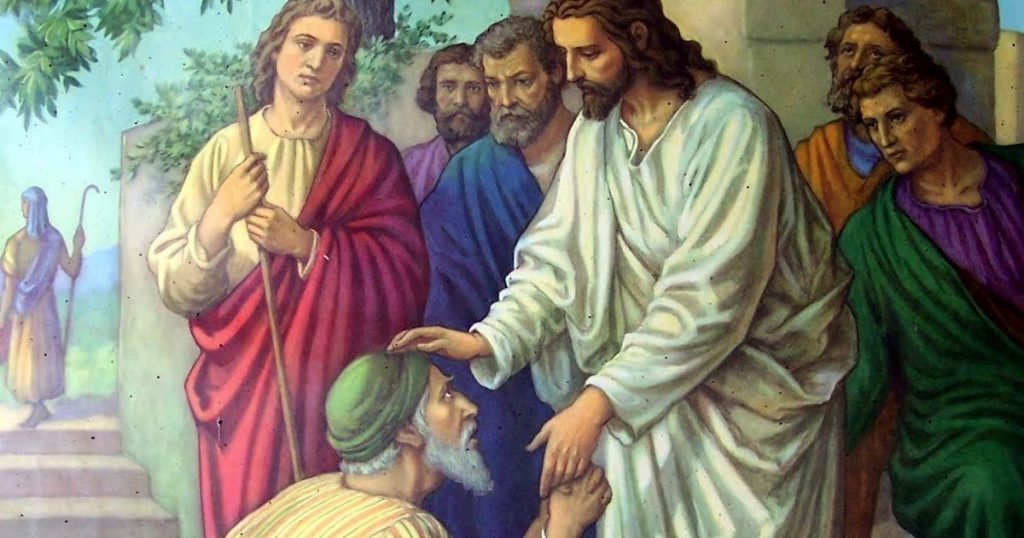

When we come to this story of the leper, and Jesus’ compassion for him, this is yet another category of the marginalized: those suffering from disease, from serious problems of health, either physical or mental. Our outreach here is then different from what we offer elsewhere, nor are we to confuse or conflate this category with the others. The lepers we encounter in the gospel are not metaphors for sinners – Jesus goes and eats dinner with “tax collectors and sinners” his outreach to them being specifically described as one of encounter and discussion, of teaching of the law and the gospel so that the sinner might repent and return to God.

Nor are they the poor: afflicted by sin, perhaps in their own bad choices, and as the victims of the aggregate of society’s sins that create an economy that does not allow them to participate positively, productively and so, give them the dignity of providing for themselves and their families.

For the person caught up in the mystery of suffering, turning in faith, like the leper who seeks out Jesus, the Christian response is not a theological lecture, but to be present to them, offering solidarity with them, and by prayer and sacrament, bringing spiritual healing, and yes, the prospect of physical and mental health by God’s grace.

That impulse to explain suffering, no better exhibited than in the famous story of Job, often leads to what Job’s so-called comforters mistakenly did: they blame Job for his troubles in their trying to make sense of the suffering of the innocent. Job, who we met in last week’s readings, was by some great gift of grace able to resist their message, maintain his faith, and sustain his hope in redemption from his suffering, and justification before God.

I don’t know how you responded to the first reading from Leviticus, that detailing of the regulations governing leprosy. One hears or reads it and can’t help but think, how cruel!

The Holy Father in his 2015 homily explained that the purpose of this legislated marginalization was “to safeguard the healthy”, “to protect the righteous”, and to “eliminate” or marginalize “the peril” by treating the diseased person harshly. That is, give that person no incentive to approach family or community, to accept their lot, and live, in this case, literally on the margins of the town or village, sustained by what food might be left for them by family and friends.

The Pope then recalls that “Jesus revolutionizes and upsets that fearful, narrow and prejudiced mentality” as understandable as it would have been.

And it was through that revolution in perception of the sick, that these were people that God desired to have cared for and included, that the whole idea of community health care came. Christians established the first hospitals, I’m sure many of you were already aware of that. The idea of medical science was then given priority in Christian society, because of the imperative that we care, cure and restore the sick to community. And one can consider the work done especially with lepers, with leper colonies maintained for centuries, and overseen by religious brothers and sisters who were committed to seeing that the afflicted did not feel abandoned, but rather loved.

Our parish’s Compassionate Care ministry is very much about this. Those who volunteer and are trained to this work with the sick, the shut-in, those struggling with depression and anxiety, those threatened by cancer and other terrible physical afflictions, strive to overcome the barriers in these situations and reestablish connection, forge the ties that bind us all in Christ.

The graces they receive are necessary in overcoming the fears that people bring to a situation of suffering.

In an age of diminished faith, there appears a psychological fear, and a lack of confidence on the part of many today to confront, in the face of those in pain, the problem of suffering. For those who’ve no spiritual tradition (Christian or otherwise) to support them, the resources are few – and it’s no wonder assisted suicide is the fastest rising cause of death in Canada. So many are terrified by suffering in illness, by sickness unto death.

As a hospital chaplain, I’ve encountered people who’ve made it to the hospital, but hesitate to go into the room, worried that they will “mess it up,” start crying, say something stupid, in some way or another upset the patient, the sick friend or relative, and they are afraid.

In my personal experience, particularly as the parent of a child with cancer, I remember how this fearful attitude presented itself in the way others were raising their children. When our daughter lay in hospital connected to a myriad of machines, all beeping away as they monitored and medicated our little six-year-old, we so hoped for her to be visited by school friends and the younger members of our family and social circle.

Some said they simply couldn’t come because it would upset their children. To see a child suffer, I would agree, is a particularly hard thing. As an on-call chaplain at McMaster Children’s hospital, I marvel at the strength of those charged with the care of our little ones knowing they face this day after day. And, by the way, I’ve known nurses and doctors, surgeons and specialists, who’ve eventually transferred out to the regular hospitals because of how hard it is to do year after year.

In the case of my daughter, a child who needed to be a child, the visit of her school friends was important. And some came. What actually happened is that they went into the hospital room, looked past all that beeping and chiming equipment, and saw Helena; and they came to play, to colour, to be children together.

That’s what the ministry to the sick is: to be children together, God’s children, adopted and made sons and daughters by his divine love.

And so indeed is the nature of this ministry, this erasing of the line between the sick and the well by being present to them, communicating to them that there is nothing that can separate us from the love of God, the love of each other in Christ; and no matter how high the walls might be in terms of illness, and the treatments, the surgeries, the therapies, the equipment, the gowns and the masks, we will find a way over or through so that no man, woman or child, no brother or sister in Christ is bereft of the comfort of prayer, the spiritual nourishment of sacrament, and the confidence that comes of the faithful gathered – that where two or three are, Jesus promises, so he will be there too.

Amen.