Mass readings for the 3rd Sunday in Lent:

Exodus 20.1-17 Psalm 19.7-10 1 Corinthians 1.18, 22-25 John 2.13-25

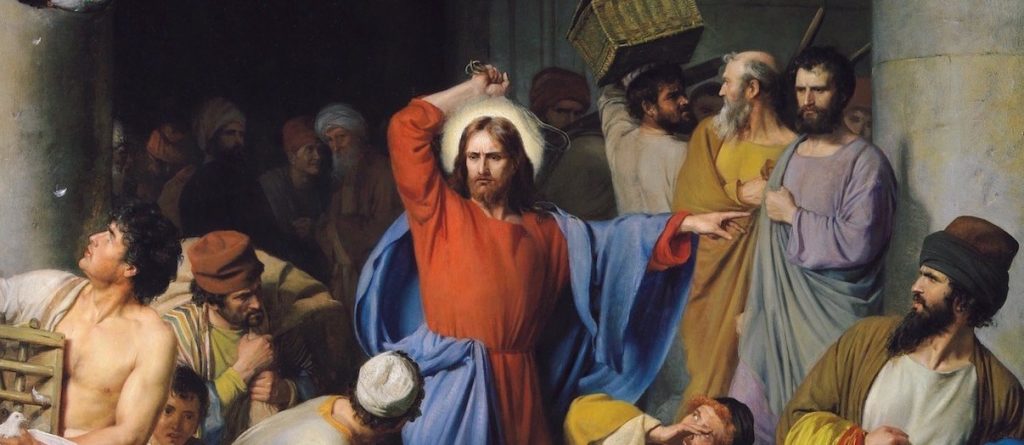

The cleansing of the Jerusalem Temple is an historical event attested to in the gospels; it’s one of the key episodes of the story of Jesus – for some scholars, this was the basis for the charges leveled against Jesus; it was for this he was condemned to death. This speculation comes of it being mentioned in the accounts of the trial found in Matthew and Mark. But the more interesting thing about these mentions is the fact of the testimony about it being confused: and it seems rather that the whole matter got dropped because Jesus’ accusers couldn’t actually work out what our Lord meant when he said that he would tear down the Temple and in three days rebuild it.

Of course, we know what he meant: he was speaking about his body. And that understanding came in retrospect; that is, at the time he said it, the disciples were equally confused. I think many are still confused, and don’t grasp fully the significance of what he said.

What Jesus had done goes beyond his announcing his imminent resurrection – its not just about what will transpire that week in Jerusalem, but rather, Jesus indicates a shift in the location of the holy in society. It goes from being a specific geographic spot, within the holy of holies, the inner sanctum of the Temple, to his body; and as we know and confess, his body in the world is wherever the Church is, wherever the faithful are, individually and collectively. Our bodies are meant to be the temple now in which the holy spirit dwells. And that is a revolutionary idea.

This shift in the locus of the sacred changes for us the interpretation of the cleansing of the temple. What was done once in the ancient city of Jerusalem, in the sacred precincts of a holy site, is now something that must now be reenacted within the new temple – the Church as the gathering of all believers, within you and I there must be a casting out of the moneychangers and the sellers. This body, your bodies and mine, are not to be marketplaces, we are not be caught up in buying and selling, consuming and trading, but rather each of us is to be a sacred place.

And that is no more welcome a message now as it was 2000 years ago. The world wants the buyers and the sellers to stay right where they are.

It is not controversial to say we live in a consumer society, that we have a consumer economy, that business and government, for all their talk of people being customers, clients, citizens, stakeholders, still has an underlying view of us all as consumers of products and services. And the great stress upon our leaders is to keep us happy by providing all these things we consume; or finding excuses for why they can’t, putting the blame on greedy big business as corporations in turn throw the blame back at government for its taxes and regulations.

Of course, we’ve been conditioned to think of ourselves this way – perhaps we would prefer to be regarded as “enlightened” or “conscientious” consumers; “green” or “ethical” consumers; but that label of “consumer” I think doesn’t sit comfortably on us. Aren’t we more than that? Aren’t we more than mouths to feed, or masses to be entertained? Aren’t we more than people who grow old and make demands on scarce health care resources? Aren’t we more than young people looking despairing at the housing market? Aren’t we more than the middle-aged worrying about our investments; that we may never retire because we can’t afford it?

Yet, here we are, and the pollsters confirm this. We are worried about all these things, our minds turned to these worries, and our hearts are within chests grown tight with anxiety. As Wordsworth famously wrote,

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers; —

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

Remember, Jesus, as this gospel passage tells us, “…knew all people and needed no one to testify about human nature, for he himself knew what was within the human person.” He knows what’s going on, the worries, the fears. And what he demonstrates in the cleansing of the temple is that this is a necessary purging of the source of our anxieties.

You see, the temple in Jerusalem while being dedicated to the one true God was nonetheless organized around principles familiar to any pagan – you secured salvation, redemption, the favour of the god, through sacrifice. Failing to sacrifice meant disaster for sure. You had to keep this enterprise going to stave off catastrophe. And what happens, quite unwittingly, is the destruction of faith through a real relationship with God, and in its place this mechanical performing of ritual, that depended upon material sacrifice, of money really at this point. The religion becomes an empty shell.

Originally, those sacrifices as prescribed in the law of Moses came from the people in a very real and sincere way. The farmer who raised the wheat, the animals, by the sweat of his brow offered something that he had tended, raised, cared for, invested himself in. To offer it up was as much a sacrifice of self as it was of the wealth these things represented. And the sacrifice really was meant to be a meal of reconciliation, of thanksgiving, of healing a rift between the person and God. But what had now come about was something that really looked more like paying taxes; no longer a gathering of friends in celebration, but a procession of the masses to pay the king’s levy or face a fine. It wasn’t about holy communion with the lord of the heavens, but paying protection money because, y’know, it would be a shame should an accident happen because you’re not paid up.

So, today, it’s not great surprise in light of these observations to note how so many Catholics come to this place, not in joy, but because of dreaded obligation; they don’t bring their hearts and minds to offer up to God, but mistake the money as the means by which they seal the deal. The faith is not lived as it was in apostolic times, in light of the resurrection; the religion, while not unimportant, is observed minimally, like their ancient forebears in Jerusalem who trudged up to the Temple – and I won’t say they didn’t have any fun at the high holidays, but just that the relationship with God had grown distant, cold, no longer enjoying the intimacy that was intended.

Now, I know that the majority here have grasped that to some degree, some more so, some less. And that also there are among us those who’ve never understood their religion as anything but a set of obligations, of duties to be performed, the joy in them more a product of them being done with family, as an ethnic tradition, than as something that actually draws from them their worries and concerns, and gives them blessed assurances of God’s love and the Holy Spirit’s presence in their lives.

The eucharist, that sacrament of the spirit, is the only thing we should truly consume and incorporate into ourselves, our souls and bodies. And so too, these souls and bodies should be what we truly offer to God on this day, through this holy season of Lent, a living sacrifice of love.

Amen.